Episode 6 in the Big Flame History series mentioned two Italian political organisations – Lotta Continua [the Struggle Continues) [LC] and Potere Operai (Workers Power) [Potop]. This post gives more information on the former.

Episode 6 in the Big Flame History series mentioned two Italian political organisations – Lotta Continua [the Struggle Continues) [LC] and Potere Operai (Workers Power) [Potop]. This post gives more information on the former.

The Beginning

In the mid 1960s a number of activist groups influenced by the Operaismo writers were established in different cities. In 1968 they moved apart following a disagreements over organisation and the importance given to struggles over wages. The Venato and Emilia-Romagna group, which adopted a more Leninist perspective and included Toni Negri, became the basis of the new national Potop. The Pisa branch of the Tuscany group, mainly ex-Italian Communist Party and including future LC General Secretary Adriano Sofri, moved to Turin attracted by the struggles at FIAT. There it linked up with students from Milan, Trento and Turin to become Lotta Continua.

The links from Lotta Continua back to Operaismo are apparent in this quote from Adriano Sofri: “The class struggle is the mainspring of development of every social system. The interest of the ruling class is to make this spring work for the extension and reinforcement of its own power. And so workers’ autonomy occurs when the class struggle stops working as the motor of capitalist development” (quoted in Radical America March-April 1973 issue p5).

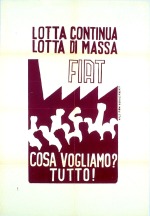

LC grew out of interventions at the FIAT Turin plant in April/May 1969. Students and activists got to know workers, started helping them write leaflets, which led on to joint assemblies. The leafleting was a large scale enterprise, with 15,000 to 20,000 handed out per shift.

The phrase “La Lotta Continua” started to appear on the leaflets (taken from “la lutte continue” from the events in France the previous year). In time it became the umbrella name for a loose network of activists. Groups in other cities started adopting the same phrase in their leaflets, and within 3 years LC was a national organisation. The newspaper “Lotta Continua” was launched in Nov 1969. By 1972 it was a daily.

The End

Lotta Continua crumbled away after its second congress in Oct/Nov 1976. A key event in the runup was when male members of LC used violence to force their way into an all-women abortion demonstration in Rome in December 1975. The congress was characterised by hostility between male workers and women, and between both and the leadership. LC later published the congress speeches as Il 2o Congresso di Lotta Continua, and a selection of these can be found in Red Notes Italy 1977-9: Living with an Earthquake pp81-96 (also available as libcom.org or Class against Class). Within months most of the organisation had dissolved into a looser movement – the area of autonomy.

China

Some commentators have labelled Lotta Continua “Soft Maoist”. Certainly like much of the “new left” groups in Europe, formed after 1968, the Chinese cultural revolution was an influence. However, despite adopting some Maoist phrases, the influence was not as strong as that of Operaismo.

Examples of overlapping terminology include references to Red Bases – taking areas of control away from the enemy (Organising for Revolution pp10-11, Fighting in the Streets p12). LC also talked of a cultural revolution occurring in the factories in Italy (see Bobbio p48). The frequent references to the masses have parallels with the ideas of the “mass line” and “serving the people”.

Take Over the City

Lotta Continua had taken up housing struggles from the early days. However in 1971 it launched “Take over the City” as its political programme. It argued “the city is merely the network of those instruments of exploitation and domination invented by the bosses for keeping the workers under their thumb and for dividing them at every moment of their existence. …There is beginning to be, today [Nov 1970], something in the social sphere, something comparable to the explosion which rocked Italian factories two years ago” (Fighting in the Streets pp2,5).

Struggles around the programme covered housing (rent strikes, occupation of empty flats), food (pickets of supermarkets, establishing “red markets”), transport (refusing to pay fares, stopping buses running), schools and nurseries.

Within a few years LC abandoned “Take over the City” as a programme (without dropping the ideas behind it), as it found that involvement in community struggles did not lead to the development of political power bases from which it could generalise out of the struggle.

Elections

The early Lotta Continua had little truck with elections, taking up the slogan “Don’t vote – occupy!” during the June 1971 regional elections (Take over the City p22). From 1973 onwards LC began to shift its stance.

In 1975 PdUP (Proletarian Unity Party) and Avanguardia Operaio (Workers Vanguard) established a joint platform – Democrazia Prolerari (Democratic Proletariat) for the regional elections. LC did not support them, advocating a vote for the Italian Communist Party (apparently on the basis that putting them in power would create a better basis for struggles). By the June 1976 national election it had joined DP (although keeping its own separate programme). The result – 550,000 votes or 1.5% of the total, 6 deputies, 1 of them from LC) was a major disappointment. Despite this being the first success at a national level for revolutionary left candidates, LC had hoped for much more.

The Composition of LC

Red Notes claim that Lotta Continua has up to 50,000 militants (Italy 1977-9: Living with an Earthquake p110). Others have challenged this figure. The early LC found it difficult to determine its numbers because of difficulties defining what was a militant. The first census in Lotta Continua’s history, around the time of the 1975 congress produced a figure of 8,000 militants, less than expected (Bobbio p148). This is the only number I have found. What is undoubtedly true is that LC had an influence beyond its size.

Information on the delegates at the two LC conferences provides a breakdown of the leading members of the organisation. At the Jan 1975 congress, delegates were 32% labourers, 7% other proletarians, 11% employees and technicians, 17% teachers, 21% students, and 11% full time militants. 20% were aged 20 or younger, 60% aged 21 to 29, and 205 30 and over. 10% of the delegates were women. These figures can be compared with a sample survey of the general membership which revealed 26% women, 27% labourers and 31% students (all data from Bobbio pp148-49).

By the last congress in Oct/Nov 1976 the percentage of women delegates had risen to 27.5%. 31% were workers, 32.3% were at university or school, and 9.6% employees of various kinds (Il 2o Congresso di Lotta Continua p306).

Criticisms of Lotta Continua

LC has been criticised for amongst other things:

– its narrow focus on a certain type of worker

– a lack of democracy in its internal organisation

– its response to feminism

– its attitude to violence

– Its neglect of theory

A lot of LC’s problems can be part explained (which isn’t the same as justified) by its relatively large size and speed of recruitment. It is significantly easier to deal with some of these issues if your group is small and homogenous, although practice shows this is certainly no guarantee! I will say something about each of the issues listed.

Narrow Focus

Lotta Continua went through many shifts in its campaigns, the social sphere, the unemployed, prisoners, etc. However, it was forever marked by its initial inspiration – workers at Northern factories like FIAT. Places where unions were weak and workers struggles strong. It struggled to generalise this experience- to deal with the lack of an imminent revolutionary upheaval, the continuing role of the Italian Communist party, etc. It did make some changes, participating in Councils of factory delegates from 1972, but never enough.

Internal Organisation

Pre LC Adriano Sofri wrote: “For us, the correctness of revolutionary leadership, strategy, and organization derives neither from past revolutionary experience nor from the consciousness that the party is necessary. Their correctness derives, in the final analysis, from their relationship to the masses, and their capacity to be the conscious and general expression of the revolutionary needs of the oppressed masses. …The problem for revolutionaries is not to “‘place yourself” at the head of the masses, but to be the head of the masses” (Sofri Organising for Workers Power). This position is often repeated e.g. “We choose to be inside the struggles which the masses are waging. …We have tied to organise our forces, rather than to discuss organisation” (Organising for Revolution pp6-7).

Lotta Continua’s organisation prior to 1973 was rudimentary. Apart from decision making at national conventions, it was run by a group of old friends (Sofri in his 1976 congress speech confessed to a “private patrimony”). Then things changed: “The theoretical and political formation of cadres, the election of leaders, the individual responsibilities of the militant in the framework of collective discipline, the division of tasks and specialisation …It is nothing else than the discovery of democratic centralism and the third-internationalist concept of the party” (Bobbio p130, translation Della Porta p88). As a result from 1973 onwards “the possibility of comrades contributing to the formation of the political line was reduced; the responsibility for the major decisions was ever more concentrated at the top of the pyramid” (Bobbio p130, translation Ginsborg p360).

In part this was response to more difficult times, but it is also a product of the way LC began. A need to find a more coherent line from the different positions of those who found themselves in the organisation. From this distance it is hard for me to condemn all the organisational changes introduced. Some must have produced a needed efficiency. However, there was clearly problem with the amount of democracy.

Response to Feminism

LC leaders admitted that they very slowly came to see the struggle against sexism as an important part of the class struggle (e.g. Guido Viale in his introduction to the 2nd congress book). Verbal violence against office workers during factory protests often had a strong sexual content. In fact Lotta Continua probably responded faster than many groups on the Italian left, which led to higher expectations, and the eventual breakup. The divisions between the workers and the women in LC were exascerated by the lack of women workers (which itself stemmed from the nature of the workforce).

Attitude to Violence

The newspaper “Lotta Continua” was known for the violent tone of its language. The death of the Police Commissioner Calabresi in 1972 (see below) was described as “a deed in which the exploited recognise their own yearnings for justice”. This stemmed from a feeling that a civil war was underway, but served to provoke further the police and fascists. The Red Brigades, and similar groups, were criticised by Lotta Continua for the opportunities they gave to the right wing and carrying out the sort of actions which could not be taken up by the masses. After 1974 LC tried to reign in the violent acts of some members e.g. by closing down the Prisons Commission. This simply escalated the departure of some members, many from the “servizio d’ordine” (defence squads initially established for protection at demonstrations) to the armed groups. NAP (Nucleus of the Armed Proletariat) was a split from Naples LC. Prima Linea (Front Line) was formed out of ex-LC members from Milan and elsewhere, plus former Potop members.

Neglect of Theory

It is certainly true that LC was practice orientated, and gave little time to explicit discussions of theory. There was still a theory underlying its actions. Whether more theoretical discussion would have made much difference to the rapid swings in approach, is difficult to judge. Certainly there are plenty of theory heavy groups who have also swung alarmingly in their positions.

After Lotta Continua

LC members went on join a variety of different groups – The Italian Socialist Party, the Radical Party and the current left coalition Rifondazione Communisti (Communist Refoundation). Several went on to work for newspapers and television.

The paper “Lotta Continua” carried on to June 1982. In 1977 it opened up its letters page and debate blossomed – mainly from the former women members and sympathetic men (the former leaders and workers were present to a much lesser extent). Personal politics came to the fore, with many confessing they were desperate and lonely. A selection of letters was published as Care Compagne, Cari Compagni. In 1980 a smaller selction was published in Britain as Dear Comrades. A Big Flame member wrote the introduction and part translated the book.

Within a decade the view of much of the Italian left was to see the former LC leaders as out of date and ridiculous (as reported in Lumley States of Emergency p278) In 1988 the former LC General Secretary Adriano Sofri was arrested on the testimony of a “pentito” (repentant) former LC member and charged with ordering the murder of a Police Commissioner Calabresi in 1972. The legal process dragged on to 2000. Then despite doubts about the testimony of the “pentito” and the lack of any other evidence, Sofri received a 22 year jail sentence. Two other former LC members were convicted at the same time. One has been released on medical grounds, another fled whilst out of jail for an appeal. Sofri is still in prison.

Archive Archie

Sources on Lotta Continua

Very little from Lotta Continua is available in English. In the early 1970s two pamphlets were published in a series Documents from the Italian Revolutionary Movement. No 1 was Organising for Revolution a reprint of a speech by Gianni Safri and Franco Caprotti of LC at a Telos conference in 1971. No2 was called Fighting in the Streets. The latter consisted of Lotta Continua documents about its “Take Over the City” programme.

This is complemented by a descriptive account of Take over the City which was published as a pamphlet in England by Rising Free and in the USA in a Radical America article. It is currently available in three places on the internet:

Radical America March-April 1973 issue (pp pp78-112 of the magazine, pp80-114 of the document)

Class Against Class

Libcom.org

The same issue of Radical America also contains an article ”Organizing for Workers Power” by Adriano Sofri, written in 1968 pre Lotta Continua (pp pp33-45 of the magazine, pp35-47 of the document) and an interview with another LC leader Guido Viale (pp pp113-119 of the magazine, pp115-121 of the document). The former has been republished by Monkraft.

The 1979 Red Notes/CSE Books pamphlet Working Class Autonomy and the Crisis includes two articles by Lotta Continua members “25 Years at FIAT” and “The Worker-Student Assemblies in Turin: 1969”.

Discussions of LC in English, particularly those from left groups, demonstrate little understanding of it. Exceptions are Paul Ginsborg A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics 1943-1988 (Penguin, 1990); Donatella Della Porta Social Movements, Political Violence and the State (CambridgeUniversity Press, 1995) and Sidney Tarrow Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy 1965-75 (Clarendon Press, 1989). All three draw heavily on Bobbio (see below), as indeed do I.

For those who can read Italian there is a considerable literature about LC e.g. Luigi Bobbio Lotta continua: storia di una organizzazione rivoluzionaria (Roma : Savelli, 1979) and Aldo Cazzullo I ragazzi che volevano fare la rivoluzione. 1968-1978: storia di Lotta continua (Milano: Mondadori, 1998).

A fairly complete run of the newspaper Lotta Continua (apart from the early years) can be found in the “Red Notes Italian Archive” at the London School of Economics.

In the early 70s there was a LC branch in London. Around 1971 it issued a leaflet come pamphlet in Italian, English and Spanish in support of a campaign for a guaranteed minimum wage of £35 a week. It was called That’s Enough! Now we want Everything.

I posted on this site a brief review of the history and positions of Lotta Continua. I then followed this up in Lotta Continua Part 2 by making available some articles written by or about Lotta Continua from the Big Flame Internal Bulletin. I now want to conclude this series (unless something more BF/LC related which I don’t know about turns up) with two items I have obtained since the last post. Another internal document and a pamphlet published by West London Big Flame.

I posted on this site a brief review of the history and positions of Lotta Continua. I then followed this up in Lotta Continua Part 2 by making available some articles written by or about Lotta Continua from the Big Flame Internal Bulletin. I now want to conclude this series (unless something more BF/LC related which I don’t know about turns up) with two items I have obtained since the last post. Another internal document and a pamphlet published by West London Big Flame.